1. The History

The history on this place is well documented but I’ve done an overview of the quarry’s history, mainly to help me get my head around the place.

Dinorwic quarry is located between Llanberis and Dinorwic, in North Wales. It covers more than 700 acres of land and at its peak, was the second largest producer of slate in the world (nearby Penrhyn was in first place). The first attempts to extract slate here commenced in 1787 when a consortium took out a lease on the site from landowner Assheton Smith. The quarry was moderately successful but ran into financial problems due to higher tax and transportation costs resulting from the Anglo-French War in the early 1800s. Post 1809, under a new business partnership headed up by Smith himself, the quarry started to flourish. The slate vein at Dinorwic is almost vertical and at or near the surface of the mountain, which allowed it to be worked via a series of stepped galleries. Quarrying was spread across a number of sites including Adelaide, Braich, Bryn Glas, Garret, Turner, Victoria, and Wellington to name but a few. This lasted until the 1830s. The construction of a 2ft-gauge horse-drawn tramway, north to Port Dinorwic in 1824, was pivotal the quarry's development. And while this solved the transportation issues for the quarries above the tramway that came in from the north-west at around 1,000ft, for the quarries below the tram line including Wellington, Ellis, Turner, Harriet and Victoria, transportation of slate remained a problem. This was solved in the 1848 when the 4ft gauge lakeside Padarn railway was built, along with the Padarn-Peris tramway extension. It remained the main transport link for the quarry before closing in 1961.

Map of Dinorwic Quarry:

The current form of the quarry is little changed from the time of the World War One, bar the enlarging of the actual quarry faces, and deepening of the sinks. The quarry was divided into two main sections, each with their own central series of inclines, traversing from the south-west upwards in a north-east direction. The Garret section had nine inclines numbered A1 to A9 with a total of 20 levels coming off them on both sides. At the bottom was Vivian Level at approximately 600ft and at the top Llangristiolus Level at 2,000ft. Gradients varied from a relatively gentle 1 in 4.1 (A3) to a very steep 1 in 2.2 (A6 and A7). South-east of Garret was the Braich section. Here there were 10 inclines numbered C1 to C10 with, like Garret, 20 levels in total. At the bottom, around the 400ft mark was Sinc Fawr and at the top end , again, the Llangristiolus Level at just under 2,000ft. Braich boasted the steepest incline (C8) at a drum house creaking 1 in 1.9. The total of 40 stepped galleries were joined by a vast internal tramway system.

At its peak, in the late 1800s, the quarry employed over 3,000 men and was producing an average of 100,000 tonnes of slate per annum. This was driven by the world-wide boom in demand for roofing tiles which were exported all over the UK, Europe, and Northern America. While the quarry’s internal tramways had utilised horsepower up until around the 1860, the quarry then started to use small steam engines. De Winton's of Caernarfon initially supplied five small vertical-boilered steam engines, and from 1870 Hunslet Engine Company also supplied engines and went on to supply over 20 engines, making them the quarry’s main engine providers. The quarry used three “class” of engines. The majority were “Alice” class which worked in and around the quarry. Two “Port” class engines were larger and designed to work at Port Dinorwic. Finally, two “Tram” or “Mills” class engines worked on marshalling duties on the Padarn–Peris Tram Line that linked the quarry mills to the Padarn Railway. As late as the 1960s the quarry still had around 20 engines on its books, but these were sold off during this decade. The final four engines were disposed of when the quarry finally closed in 1969.

Built in 1898, George B working at the quarry in 1966 (now rebuilt and in steam at Bala Lake Railway):

© Unknown

Quarrymen with a loaded 'flat car' of slate - 'slediad' - ready to be transported to the splitting and dressing sheds, Dinorwic Quarry, early 1960s:

© Emrys Jones

And team shot of Dinorwic slate miners, circa 1960:

© Emrys Jones

After World War One the demand for slate had peaked and the slow decline started. By 1930 the workforce employed at the quarry had dropped to 2,000 and continued to fall both pre- and post-World War Two. During the 50s and 60s it become increasingly difficult to extract any more slate from the already sheer rock galleries. This was down, in part, to 170 years of unsystematically dumped slate waste which had begun to slide into some of the quarry’s major pit workings. This and a further decline in the demand for slate meant the writing was on the wall for the quarry and the Welsh slate industry in general. The final nail in the coffin for Dinorwic was “The Great Fall” of 1966 in the Garret area of the quarry. It resulted in production almost ceasing permanently. However, production did restart briefly via clearing some of the waste from the Garret fall. It required a new access road from the terraces to the rock fall but the yield was small and all production stopped in 1969.

The quarry has since been partly reused as part of the Dinorwic power station, a pumped storage hydroelectric scheme. Construction of ‘Electric Mountain’ began in 1974 and was welcomed by the community for its employment opportunities it porvided for the surrounding area. Opening in 1984, it is regarded as one of the most imaginative engineering and environmental projects of its time. The quarry's workshop at Gilfach Ddu were acquired by the council and leased to the National Museum and Galleries of Wales. It now houses the National Slate Museum.

An interesting video on Dinorwic including archive footage and interviews with ex-slate miners:

This diagram drawn by I.C. Castledine is a useful summary of the different levels and inclines

Finally, here’s a really useful overlay for Google Maps to help you find stuff:

2. The Explore

Didn’t have the luxury of a full day to explore here when I was staying nearby on a family holiday back in July and having my interest in all thinks slate piqued, I decided to go for a day trip here. It was a long day. It is just under a three-hour drive from home so with a six-hour round trip it left myself and my non-forum member mate Gazza around five hours to explore.

We’d watched the weather and the day we’d pencilled in was looking OK so off we set. Having parked up it was an easy walk onto the mid-levels. Given our relatively limited time we wanted to get the most out of our trip so a big up to @The Lone Ranger for the intel. Much appreciated mate. We decided to concentrate of the Braich side and make our way up to the Australia level by following the old quarryman’s path (known as The Fox’s steps) that link the Penrhydd Level with Pen Garret. That way, despite neglecting the Garret side, we’d get to see the main ‘tourist’ sites. In the end we stopped at the Australia level and made our way back down the way we’d gone up down the steps. We then popped down the path from the mid-level mills to check out the Anglesey Barracks area.

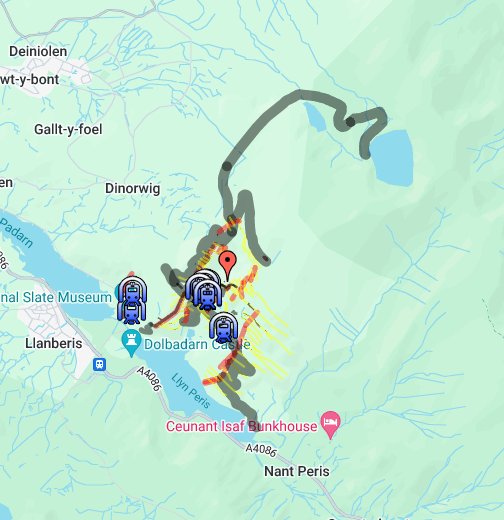

Here's a map of the key points we looked at:

In the end it worked out well as over the space of five hours we saw a good amount of the main sights. The strange thing was that we’d seen quite a lot of people who’d hopped the fence and were milling around the Penrhydd area. However, once we started up The Fox’s Steps, we didn’t see a soul until we came back down again, bar our constant sheep companions and some very smelly rutting welsh mountain goats!

3. The Pictures

There was quite a lot to whittle down into a report. Apologies that the report is still pretty image heavy. I’ve ordered the shots by level/height and hence into three sections: lower, middle, and upper.

(a) Lower Levels

The base of the quarry and the bottom of the Hydro Electric Power Station:

An area of igneous rock known as “Ceiliog Mawr” (The Cockerel) where the slate around it has been quarried away just leaving the rock.

Bottom right here is the Ponc Wyllt Incline. A "Vertical Lift" that joined the galleries Ponc Wyllt and Ponc Fawr galleries, located in the Wellington District:

Looking across to the Wellington (near) and Matilda (distant) areas of the quarry:

Miner’s accommodation near Anglesey barracks on the Bonc Moses level :

Anglesey Barracks:

Many of the quarry’s workers either lived locally or caught the quarry train on the Padarn Railway. Others came from further afield and Anglesey, in particular, and required accommodation at the quarry each week, leaving home early on Monday and returning home Saturday afternoon. Anglesey Barracks on the Bonc Moses level provided them with such accommodation. This barracks consisted of two identical blocks of 11 dwellings facing each other across. Each single-story dwelling consisted of a living room with fireplace and a bedroom for four men. The accommodation was rudimentary as there was no electricity, toilets or running water. In 1948 the local Public Health Inspector condemned the barracks as “unfit for human habitation” and they were closed down, to be left abandoned ever since.

The slate topped fireplace:

A3 Drum House in the Lower Wellington District:

A double-height rubbish wagon minus its wheels and bearings, sitting at the bottom of the A4 incline on the Pen Diphwys level:

The main thing I missed out on the lower levels was the Ponc Robin Rabera combined compressor/workshop/transformer house. It was built in 1938 to supply compressed air to the galleries on the lower levels. By the time I saw its roof sticking out of the trees I was a long way back up and I wasn’t going back down and up again!

(b) Middle Levels

General View over Garret:

At approximately 1,000ft above sea level, this level was also referred to as the “mills level”.

The massive No 3 Shed Mills opened in January 1927 (although the date stone makes reference to 1925). They were the largest of the three mills with its 60 sawing tables and 60 dressing machines. On a weekly basis, the quarrymen teams would bring and stack their finished slates in shoulder-high piles, into the open area next to No 3 Shed.

The nearby No 1 and 2 sheds, built in 1906 with a further 58 saws and 36 dressing machines between them appear to have disappeared.

The history on this place is well documented but I’ve done an overview of the quarry’s history, mainly to help me get my head around the place.

Dinorwic quarry is located between Llanberis and Dinorwic, in North Wales. It covers more than 700 acres of land and at its peak, was the second largest producer of slate in the world (nearby Penrhyn was in first place). The first attempts to extract slate here commenced in 1787 when a consortium took out a lease on the site from landowner Assheton Smith. The quarry was moderately successful but ran into financial problems due to higher tax and transportation costs resulting from the Anglo-French War in the early 1800s. Post 1809, under a new business partnership headed up by Smith himself, the quarry started to flourish. The slate vein at Dinorwic is almost vertical and at or near the surface of the mountain, which allowed it to be worked via a series of stepped galleries. Quarrying was spread across a number of sites including Adelaide, Braich, Bryn Glas, Garret, Turner, Victoria, and Wellington to name but a few. This lasted until the 1830s. The construction of a 2ft-gauge horse-drawn tramway, north to Port Dinorwic in 1824, was pivotal the quarry's development. And while this solved the transportation issues for the quarries above the tramway that came in from the north-west at around 1,000ft, for the quarries below the tram line including Wellington, Ellis, Turner, Harriet and Victoria, transportation of slate remained a problem. This was solved in the 1848 when the 4ft gauge lakeside Padarn railway was built, along with the Padarn-Peris tramway extension. It remained the main transport link for the quarry before closing in 1961.

Map of Dinorwic Quarry:

The current form of the quarry is little changed from the time of the World War One, bar the enlarging of the actual quarry faces, and deepening of the sinks. The quarry was divided into two main sections, each with their own central series of inclines, traversing from the south-west upwards in a north-east direction. The Garret section had nine inclines numbered A1 to A9 with a total of 20 levels coming off them on both sides. At the bottom was Vivian Level at approximately 600ft and at the top Llangristiolus Level at 2,000ft. Gradients varied from a relatively gentle 1 in 4.1 (A3) to a very steep 1 in 2.2 (A6 and A7). South-east of Garret was the Braich section. Here there were 10 inclines numbered C1 to C10 with, like Garret, 20 levels in total. At the bottom, around the 400ft mark was Sinc Fawr and at the top end , again, the Llangristiolus Level at just under 2,000ft. Braich boasted the steepest incline (C8) at a drum house creaking 1 in 1.9. The total of 40 stepped galleries were joined by a vast internal tramway system.

At its peak, in the late 1800s, the quarry employed over 3,000 men and was producing an average of 100,000 tonnes of slate per annum. This was driven by the world-wide boom in demand for roofing tiles which were exported all over the UK, Europe, and Northern America. While the quarry’s internal tramways had utilised horsepower up until around the 1860, the quarry then started to use small steam engines. De Winton's of Caernarfon initially supplied five small vertical-boilered steam engines, and from 1870 Hunslet Engine Company also supplied engines and went on to supply over 20 engines, making them the quarry’s main engine providers. The quarry used three “class” of engines. The majority were “Alice” class which worked in and around the quarry. Two “Port” class engines were larger and designed to work at Port Dinorwic. Finally, two “Tram” or “Mills” class engines worked on marshalling duties on the Padarn–Peris Tram Line that linked the quarry mills to the Padarn Railway. As late as the 1960s the quarry still had around 20 engines on its books, but these were sold off during this decade. The final four engines were disposed of when the quarry finally closed in 1969.

Built in 1898, George B working at the quarry in 1966 (now rebuilt and in steam at Bala Lake Railway):

© Unknown

Quarrymen with a loaded 'flat car' of slate - 'slediad' - ready to be transported to the splitting and dressing sheds, Dinorwic Quarry, early 1960s:

© Emrys Jones

And team shot of Dinorwic slate miners, circa 1960:

© Emrys Jones

After World War One the demand for slate had peaked and the slow decline started. By 1930 the workforce employed at the quarry had dropped to 2,000 and continued to fall both pre- and post-World War Two. During the 50s and 60s it become increasingly difficult to extract any more slate from the already sheer rock galleries. This was down, in part, to 170 years of unsystematically dumped slate waste which had begun to slide into some of the quarry’s major pit workings. This and a further decline in the demand for slate meant the writing was on the wall for the quarry and the Welsh slate industry in general. The final nail in the coffin for Dinorwic was “The Great Fall” of 1966 in the Garret area of the quarry. It resulted in production almost ceasing permanently. However, production did restart briefly via clearing some of the waste from the Garret fall. It required a new access road from the terraces to the rock fall but the yield was small and all production stopped in 1969.

The quarry has since been partly reused as part of the Dinorwic power station, a pumped storage hydroelectric scheme. Construction of ‘Electric Mountain’ began in 1974 and was welcomed by the community for its employment opportunities it porvided for the surrounding area. Opening in 1984, it is regarded as one of the most imaginative engineering and environmental projects of its time. The quarry's workshop at Gilfach Ddu were acquired by the council and leased to the National Museum and Galleries of Wales. It now houses the National Slate Museum.

An interesting video on Dinorwic including archive footage and interviews with ex-slate miners:

This diagram drawn by I.C. Castledine is a useful summary of the different levels and inclines

Finally, here’s a really useful overlay for Google Maps to help you find stuff:

2. The Explore

Didn’t have the luxury of a full day to explore here when I was staying nearby on a family holiday back in July and having my interest in all thinks slate piqued, I decided to go for a day trip here. It was a long day. It is just under a three-hour drive from home so with a six-hour round trip it left myself and my non-forum member mate Gazza around five hours to explore.

We’d watched the weather and the day we’d pencilled in was looking OK so off we set. Having parked up it was an easy walk onto the mid-levels. Given our relatively limited time we wanted to get the most out of our trip so a big up to @The Lone Ranger for the intel. Much appreciated mate. We decided to concentrate of the Braich side and make our way up to the Australia level by following the old quarryman’s path (known as The Fox’s steps) that link the Penrhydd Level with Pen Garret. That way, despite neglecting the Garret side, we’d get to see the main ‘tourist’ sites. In the end we stopped at the Australia level and made our way back down the way we’d gone up down the steps. We then popped down the path from the mid-level mills to check out the Anglesey Barracks area.

Here's a map of the key points we looked at:

In the end it worked out well as over the space of five hours we saw a good amount of the main sights. The strange thing was that we’d seen quite a lot of people who’d hopped the fence and were milling around the Penrhydd area. However, once we started up The Fox’s Steps, we didn’t see a soul until we came back down again, bar our constant sheep companions and some very smelly rutting welsh mountain goats!

3. The Pictures

There was quite a lot to whittle down into a report. Apologies that the report is still pretty image heavy. I’ve ordered the shots by level/height and hence into three sections: lower, middle, and upper.

(a) Lower Levels

The base of the quarry and the bottom of the Hydro Electric Power Station:

An area of igneous rock known as “Ceiliog Mawr” (The Cockerel) where the slate around it has been quarried away just leaving the rock.

Bottom right here is the Ponc Wyllt Incline. A "Vertical Lift" that joined the galleries Ponc Wyllt and Ponc Fawr galleries, located in the Wellington District:

Looking across to the Wellington (near) and Matilda (distant) areas of the quarry:

Miner’s accommodation near Anglesey barracks on the Bonc Moses level :

Anglesey Barracks:

Many of the quarry’s workers either lived locally or caught the quarry train on the Padarn Railway. Others came from further afield and Anglesey, in particular, and required accommodation at the quarry each week, leaving home early on Monday and returning home Saturday afternoon. Anglesey Barracks on the Bonc Moses level provided them with such accommodation. This barracks consisted of two identical blocks of 11 dwellings facing each other across. Each single-story dwelling consisted of a living room with fireplace and a bedroom for four men. The accommodation was rudimentary as there was no electricity, toilets or running water. In 1948 the local Public Health Inspector condemned the barracks as “unfit for human habitation” and they were closed down, to be left abandoned ever since.

The slate topped fireplace:

A3 Drum House in the Lower Wellington District:

A double-height rubbish wagon minus its wheels and bearings, sitting at the bottom of the A4 incline on the Pen Diphwys level:

The main thing I missed out on the lower levels was the Ponc Robin Rabera combined compressor/workshop/transformer house. It was built in 1938 to supply compressed air to the galleries on the lower levels. By the time I saw its roof sticking out of the trees I was a long way back up and I wasn’t going back down and up again!

(b) Middle Levels

General View over Garret:

At approximately 1,000ft above sea level, this level was also referred to as the “mills level”.

The massive No 3 Shed Mills opened in January 1927 (although the date stone makes reference to 1925). They were the largest of the three mills with its 60 sawing tables and 60 dressing machines. On a weekly basis, the quarrymen teams would bring and stack their finished slates in shoulder-high piles, into the open area next to No 3 Shed.

The nearby No 1 and 2 sheds, built in 1906 with a further 58 saws and 36 dressing machines between them appear to have disappeared.

Last edited: