1. The History

The history on this place is well documented but I’ve done an overview of the quarry’s history, mainly to help me get my head around the place.

Dinorwic quarry is located between Llanberis and Dinorwic, in North Wales. It covers more than 700 acres of land and at its peak, was the second largest producer of slate in the world (nearby Penrhyn was in first place). The first attempts to extract slate here commenced in 1787 when a consortium took out a lease on the site from landowner Assheton Smith. The quarry was moderately successful but ran into financial problems due to higher tax and transportation costs resulting through the Anglo-French War in the early 1800s. Post 1809, under a new business partnership headed up by Smith himself, the quarry started to flourish. The slate vein at Dinorwic is almost vertical and at or near the surface of the mountain, which allowed it to be worked via a series of stepped galleries. Quarrying was spread across a number of sites including Adelaide, Braich, Bryn Glas, Garrett, Turner, Victoria, and Wellington to name but a few. This lasted until the 1830s. The construction of a 2ft-gauge horse-drawn tramway, north to Port Dinorwic in 1824, was pivotal in this success. And while this solved the transportation for the quarries above the tramway that came in from the north-west at around 1,000ft, for the quarries below the tram line including Wellington, Ellis, Turner, Harriet and Victoria, transportation of slate remained an issue. This was solved in the 1848 when the lakeside 4ft gauge Padarn railway was built, along with the Padarn-Peris tramway extension. It remained the main transport link for the quarry before closing in 1961.

Map of Dinorwic Quarry:

The current form of the quarry is little changed from that of the time of the World War One, apart from the enlarging of the actual quarry faces, and deepening of the sinks. The quarry was divided into two main sections centred each with their own series of inclines, traversing from the south-west upwards in a north-east direction. The Garret section had nine inclines numbered A1 to A9 with a total of 20 levels coming off them on both sides. At the bottom was Vivian Level at approximately 600ft and at the top Llangristiolus Level at 2,000ft. Gradients varied from a relatively gentile 1 in 4.1 (A3) to a very steep 1 in 2.2 (A6 and A7). South-east of Garret was the Braich section. Here there were 10 inclines numbered C1 to C10 with, like Garret, 20 levels in total. At the bottom, around the 400ft mark was Sinc Fawr and at the top end and, again, at the top Llangristiolus Level at just under 2,000ft. Braich boasted the steepest incline (C8) at a drum house creaking 1 in 1.9. The total of 40 stepped galleries were joined by a vast internal tramway system.

At its peak, in the late 1800s, the quarry employed over 3,000 men and was producing an average of 100,000 tonnes of slate per annum. This was linked to the world-wide boom in demand for roofing slate roofing tiles which were exported all over the UK, Europe, and Northern America. While the quarry’s internal tramways had utilised horsepower up until around the 1860, the quarry then started to use small steam engines. De Winton's of Caernarfon initially supplied five small vertical-boilered steam engines, and from 1870 Hunslet Engine Company also supplied engines and went on to supply over 20 engines, making them the quarry’s main engine providers. The quarry used three “class” of engines. The majority were “Alice” class and worked in and around the quarry. Two “Port” class engines were larger and designed to work at Port Dinorwic. Finally, two “Tram” or “Mills” class worked on marshalling duties on the Padarn–Peris Tram Line that linked the quarry mills to the Padarn Railway. As late as the 1960s the quarry still had around 20 engines, but these were sold off during the decade. The final four engines were sold off when the quarry finally closed in 1969.

Built in 1898, George B working at the quarry in 1966 (now rebuilt and in steam at Bala Lake Railway):

© Unknown

Quarrymen with a loaded 'flat car' of slate - 'slediad' - ready to be transported to the splitting and dressing sheds, Dinorwic Quarry, early 1960s:

© Emrys Jones

And team shot of Dinorwic slate miners, circa 1960:

© Emrys Jones

After World War One the demand for slate had peaked and started a slow decline. By 1930 the workforce employed at the quarry had dropped to 2,000 and continued to fall both pre- and post-World War Two. During the 50s and 60s it become increasingly difficult to extract any more slate from the already sheer rock galleries. This was down, in part, to 170 years of unsystematically dumped slate waste which had begun to slide into some of the quarry’s major pit workings. This and further decline in the demand for slate meant the writing was on the wall for the quarry and the Welsh slate industry in general. The final nail in the coffin for Dinorwic was “The Great Fall” of 1966 in the Garret area of the quarry. It resulted in production almost ceasing permanently. However, production did restart via clearing some of the waste from the Garret fall. Required a new access road from the terraces to the rock fall, the yield was small, and all production stopped in 1969.

The quarry has since been partly reused as part of the Dinorwic power station, a pumped storage hydroelectric scheme. Construction of ‘Electric Mountain’ began in 1974 and was welcomed by the community for its employment opportunities for the area. Opening in 1984, it is regarded as one of the most imaginative engineering and environmental projects of its time. The quarry's workshop at Gilfach Ddu were acquired by the council and leased to the National Museum and Galleries of Wales. It now houses the National Slate Museum.

As of 28th July, 2021 now comes under the UNESCO heritage status granted to “The Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales”. It details six specific areas and Maenofferen is included as the second location described as “Dinorwig Slate Quarry Mountain Landscape”. How this will play out in terms of access to the quarry etc remains to be seen. More info HERE

An interesting video on Dinorwic including archive footage and interviews with ex-slate miners:

This diagram drawn by I.C. Castledine is a useful summary of the different levels and inclines

Dinorwic names by INNES, on Flickr

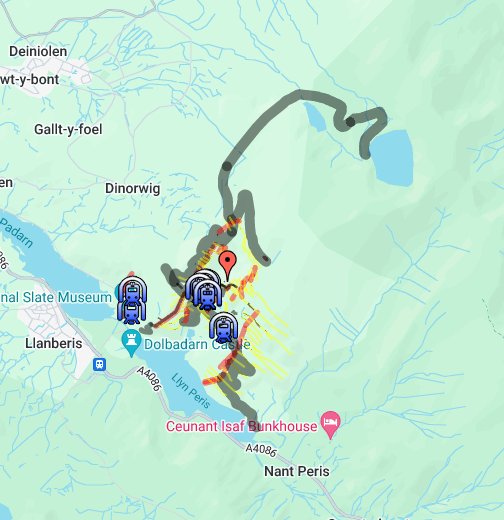

Finally, here’s a really useful overlay for Google Maps to help you find stuff:

2. The Explore

Revisit this one. Last time we did the Full Monty, all the way up to the higher levels. See the archive report HERE

This time it was a totally different affair. Visited the area with the family to look at the National Slate Museum (much recommended). After we headed up to the mid-levels for a walk. So, this is more of the “tourist trail”. Funnily enough we didn’t walk the full path across the mid-levels on my first visit so alot of this walk was new. It had been my intention to drive over early one morning to check out the less visited Garret side, but with a trip of over one hour one way, it made it difficult to do easily in a morning. Hence settled for a mid-level amble. Not as spectacular as going up to the higher reaches of the quarry but interesting in terms of this is what non-explorer/walker types would see of this amazing place, which is still pretty damn amazing.

3. The Pictures

View from the road:

Braich side incline:

The landscape changed forever:

The impressive Vivian quarry:

Looking up to Australia Level:

Start of the mid-levels walk:

At approximately 1,000ft above sea level, this level was also referred to as the “mills level”.

The massive No 3 Shed Mills opened in January 1927 (although the date stone makes reference to 1925). They were the largest of the three mills with its 60 sawing tables and 60 dressing machines. On a weekly basis, the quarrymen teams would bring and stack their finished slates in shoulder-high piles, into the open area next to No 3 Shed.

The substation:

The impressive Garret incline:

The Penrhydd incline including the now rusted horizontal incline platforms which would have taken two wagons at a time:

A nearby powder house:

Side view of the Garret incline:

The history on this place is well documented but I’ve done an overview of the quarry’s history, mainly to help me get my head around the place.

Dinorwic quarry is located between Llanberis and Dinorwic, in North Wales. It covers more than 700 acres of land and at its peak, was the second largest producer of slate in the world (nearby Penrhyn was in first place). The first attempts to extract slate here commenced in 1787 when a consortium took out a lease on the site from landowner Assheton Smith. The quarry was moderately successful but ran into financial problems due to higher tax and transportation costs resulting through the Anglo-French War in the early 1800s. Post 1809, under a new business partnership headed up by Smith himself, the quarry started to flourish. The slate vein at Dinorwic is almost vertical and at or near the surface of the mountain, which allowed it to be worked via a series of stepped galleries. Quarrying was spread across a number of sites including Adelaide, Braich, Bryn Glas, Garrett, Turner, Victoria, and Wellington to name but a few. This lasted until the 1830s. The construction of a 2ft-gauge horse-drawn tramway, north to Port Dinorwic in 1824, was pivotal in this success. And while this solved the transportation for the quarries above the tramway that came in from the north-west at around 1,000ft, for the quarries below the tram line including Wellington, Ellis, Turner, Harriet and Victoria, transportation of slate remained an issue. This was solved in the 1848 when the lakeside 4ft gauge Padarn railway was built, along with the Padarn-Peris tramway extension. It remained the main transport link for the quarry before closing in 1961.

Map of Dinorwic Quarry:

The current form of the quarry is little changed from that of the time of the World War One, apart from the enlarging of the actual quarry faces, and deepening of the sinks. The quarry was divided into two main sections centred each with their own series of inclines, traversing from the south-west upwards in a north-east direction. The Garret section had nine inclines numbered A1 to A9 with a total of 20 levels coming off them on both sides. At the bottom was Vivian Level at approximately 600ft and at the top Llangristiolus Level at 2,000ft. Gradients varied from a relatively gentile 1 in 4.1 (A3) to a very steep 1 in 2.2 (A6 and A7). South-east of Garret was the Braich section. Here there were 10 inclines numbered C1 to C10 with, like Garret, 20 levels in total. At the bottom, around the 400ft mark was Sinc Fawr and at the top end and, again, at the top Llangristiolus Level at just under 2,000ft. Braich boasted the steepest incline (C8) at a drum house creaking 1 in 1.9. The total of 40 stepped galleries were joined by a vast internal tramway system.

At its peak, in the late 1800s, the quarry employed over 3,000 men and was producing an average of 100,000 tonnes of slate per annum. This was linked to the world-wide boom in demand for roofing slate roofing tiles which were exported all over the UK, Europe, and Northern America. While the quarry’s internal tramways had utilised horsepower up until around the 1860, the quarry then started to use small steam engines. De Winton's of Caernarfon initially supplied five small vertical-boilered steam engines, and from 1870 Hunslet Engine Company also supplied engines and went on to supply over 20 engines, making them the quarry’s main engine providers. The quarry used three “class” of engines. The majority were “Alice” class and worked in and around the quarry. Two “Port” class engines were larger and designed to work at Port Dinorwic. Finally, two “Tram” or “Mills” class worked on marshalling duties on the Padarn–Peris Tram Line that linked the quarry mills to the Padarn Railway. As late as the 1960s the quarry still had around 20 engines, but these were sold off during the decade. The final four engines were sold off when the quarry finally closed in 1969.

Built in 1898, George B working at the quarry in 1966 (now rebuilt and in steam at Bala Lake Railway):

© Unknown

Quarrymen with a loaded 'flat car' of slate - 'slediad' - ready to be transported to the splitting and dressing sheds, Dinorwic Quarry, early 1960s:

© Emrys Jones

And team shot of Dinorwic slate miners, circa 1960:

© Emrys Jones

After World War One the demand for slate had peaked and started a slow decline. By 1930 the workforce employed at the quarry had dropped to 2,000 and continued to fall both pre- and post-World War Two. During the 50s and 60s it become increasingly difficult to extract any more slate from the already sheer rock galleries. This was down, in part, to 170 years of unsystematically dumped slate waste which had begun to slide into some of the quarry’s major pit workings. This and further decline in the demand for slate meant the writing was on the wall for the quarry and the Welsh slate industry in general. The final nail in the coffin for Dinorwic was “The Great Fall” of 1966 in the Garret area of the quarry. It resulted in production almost ceasing permanently. However, production did restart via clearing some of the waste from the Garret fall. Required a new access road from the terraces to the rock fall, the yield was small, and all production stopped in 1969.

The quarry has since been partly reused as part of the Dinorwic power station, a pumped storage hydroelectric scheme. Construction of ‘Electric Mountain’ began in 1974 and was welcomed by the community for its employment opportunities for the area. Opening in 1984, it is regarded as one of the most imaginative engineering and environmental projects of its time. The quarry's workshop at Gilfach Ddu were acquired by the council and leased to the National Museum and Galleries of Wales. It now houses the National Slate Museum.

As of 28th July, 2021 now comes under the UNESCO heritage status granted to “The Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales”. It details six specific areas and Maenofferen is included as the second location described as “Dinorwig Slate Quarry Mountain Landscape”. How this will play out in terms of access to the quarry etc remains to be seen. More info HERE

An interesting video on Dinorwic including archive footage and interviews with ex-slate miners:

This diagram drawn by I.C. Castledine is a useful summary of the different levels and inclines

Dinorwic names by INNES, on Flickr

Finally, here’s a really useful overlay for Google Maps to help you find stuff:

2. The Explore

Revisit this one. Last time we did the Full Monty, all the way up to the higher levels. See the archive report HERE

This time it was a totally different affair. Visited the area with the family to look at the National Slate Museum (much recommended). After we headed up to the mid-levels for a walk. So, this is more of the “tourist trail”. Funnily enough we didn’t walk the full path across the mid-levels on my first visit so alot of this walk was new. It had been my intention to drive over early one morning to check out the less visited Garret side, but with a trip of over one hour one way, it made it difficult to do easily in a morning. Hence settled for a mid-level amble. Not as spectacular as going up to the higher reaches of the quarry but interesting in terms of this is what non-explorer/walker types would see of this amazing place, which is still pretty damn amazing.

3. The Pictures

View from the road:

Braich side incline:

The landscape changed forever:

The impressive Vivian quarry:

Looking up to Australia Level:

Start of the mid-levels walk:

At approximately 1,000ft above sea level, this level was also referred to as the “mills level”.

The massive No 3 Shed Mills opened in January 1927 (although the date stone makes reference to 1925). They were the largest of the three mills with its 60 sawing tables and 60 dressing machines. On a weekly basis, the quarrymen teams would bring and stack their finished slates in shoulder-high piles, into the open area next to No 3 Shed.

The substation:

The impressive Garret incline:

The Penrhydd incline including the now rusted horizontal incline platforms which would have taken two wagons at a time:

A nearby powder house:

Side view of the Garret incline:

Last edited: